From the series “Dispatches: Backgrounders in Canadian Military History”

(Note that some of the content in this series is outdated and is under review.)

The South African War of 1899-1902 or, as it is more commonly known, the Boer War, occasioned Canada’s first major military expedition abroad. In some ways the war would be similar to the conflicts waged in the century just ending; in others it would anticipate the nature of modern warfare in the bloody century to come.

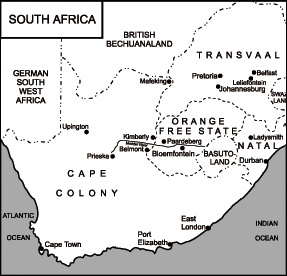

The South African War had its origins in more than sixty years of strain and hostility between the British in South Africa, concentrated in their possessions of Cape Colony and Natal, and the descendants of the region’s first Dutch settlers, known as Boers (from the Dutch for farmer), centered in the more northerly independent republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. The discovery of gold in the Transvaal in 1886 resulted in the influx of a large fortune-seeking group called uitlanders (foreigners) who were mostly of British origin. Doubtful of their loyalty, the Transvaal government refused to grant them political rights. For Britain, the plight of this group was a major cause of the war.

At the height of its power in 1899, Britain viewed the largely agrarian and religiously conservative Boers as backward-looking, and an obstacle to larger British political and economic ambitions in the region. Important British authorities even hoped for a war, which they thought they could easily win, to resolve the Boer problem once and for all by incorporating them into a pan-British South Africa. Matters came to a head in 1899 when Britain began reinforcing its military garrison in South Africa. On 9 October, the Transvaal government issued an ultimatum demanding that this build-up cease. London did not reply, and on 11 October the Boers declared war.

In Canada, a self-governing member state of the British Empire, affection for Britain had always been strong. It had possibly never been stronger than at the war’s outbreak, which came just two years after the extravagant celebrations surrounding Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. During the months preceding the war, the English-Canadian press had been full of pro-British and anti-Boer articles, many of them urging Ottawa to dispatch Canadian troops in the event of a conflict. After the Boers declared war, such pressure intensified. French Canada, together with some vocal English Canadian labour organizations and farmers’ groups, remained opposed. Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier had political and constitutional reservations about Canadian involvement, and was especially concerned about the opposition emanating from Quebec.

The eloquent French-Canadian nationalist, Henri Bourassa, led this opposition. Suspicious of the aims of British imperialism, Bourassa feared that Canadian participation would set a precedent for involvement in future conflicts. While French-Canadian opinion was certainly not monolithic on the issue, the majority supported Bourassa’s views and saw Canada’s entry into the war as an act of subservience to the Empire. Canada, Bourassa argued, should go to war purely on the basis of its own national interests.

In the end, Laurier bowed to pressure from more populous English Canada, particularly Ontario, and agreed to send troops, but it would not be an open-ended commitment. Canada would foot the bill for a small, all-volunteer force, and pay for its recruitment and transportation to South Africa. Once there, it would become the financial responsibility of Great Britain.

The first Canadian contingent consisted of the Second (Special Service) Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry (2 RCRI). Under the command of the country’s most experienced professional soldier, Lieutenant-Colonel William Dillon Otter, the battalion arrived in South Africa on 29 November 1899. Consisting of eight 125-man regionally-based companies, one from western Canada, three from Ontario, and two each from Quebec and the Maritimes, they were on arrival “capable of not much more than forming ranks and marching without getting out of step too often”. They were nonetheless to fight a bitter battle against the Boers at Paardeberg less than three months later.

The war can be divided into three distinct phases. The first lasted from October 1899 to January 1900, and saw the Boers advance into British territory and score several impressive victories. The British were confronted with the grim realities of the modern battlefield, which modern high-powered weapons had transformed into a lethal killing-zone. Although on the strategic defensive, the British took the tactical offensive, and brave but foolhardy charges by British regular soldiers against well-sited Boer positions resulted in startlingly high casualties for the attackers and remarkably low ones for the defenders. At Colenso on 15 December 1899, for example, the British lost 1139 dead, the Boers just 29.

The second phase of the war lasted from February to June 1900 and saw the British launch a counter-offensive, advance through the Orange Free State, and capture the Transvaal’s capital, Pretoria. It was during this phase that 2 RCRI first met the enemy in battle.

A Boer force of over 4000 under Piet Cronje, fleeing eastwards from Kimberley to Bloemfontein, had been halted by British cavalry and forced to form their wagons into a defensive position, or laager, near Paardeberg Drift on the north bank of the Modder River. A British force of about 30,000 infantry, including 31 officers and 866 men of 2 RCRI, attacked this position on 18 February 1900. The Canadians experienced their first casualties early in the morning after crossing the Modder and advancing towards the Boer lines. More came that afternoon. Participating in an ill-conceived and unsuccessful charge ordered by the acting British commander, Lord Herbert Kitchener, the regiment lost 18 dead and 63 wounded.

The badly outnumbered Boers held on, but soon reached the end of their endurance. On the night of 26-27 February, the Canadians led what the commander-in-chief, Lord Frederick Roberts, hoped would be the final assault. As they quietly made their way through the darkness, near the enemy lines someone struck a trip wire, prompting a Boer fusillade. The men hit the ground and, due to a confusion in orders, began to retreat. Two companies remained in place, however, and they continued to pour a steady fire into the Boer encampment. Realizing his position was hopeless, the beleaguered Cronje raised the flag of surrender later that morning.

Paardeberg was the first Boer defeat, and a major one. Roughly 10 per cent of their total manpower became prisoners of war. Canadians played a leading part in achieving this victory, with Lord Roberts enthusing that “Canadian now stands for bravery, dash, and courage”. Close examination of the battalion’s performance at Paardeberg underlines its inexperience, but Canada hailed the battle as a great national triumph, with one observer calling 2 RCRI “the fighting germ at the heart of the British army”.

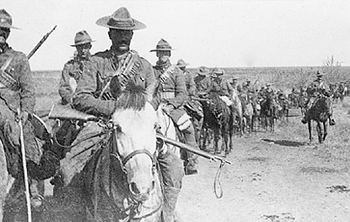

After the fall of Pretoria in June, the war entered its third, longest, and most controversial phase. From then until its end in May 1902 it took on the characteristics of a guerrilla struggle. Boer mounted units called commandos disappeared into vast open spaces of the veldt, their tactics focusing on sudden and bloody attacks and swift withdrawals.

Determined that the most effective means of dealing with the elusive commandos was to destroy the basis of the Boer domestic economy, the British sectioned off large portions of the veldt with barbed wire, anchored by specially-built blockhouses. Columns of soldiers proceeded through each section burning farms and homesteads, and rounding up whatever Boers they could find, mostly women and children, for dispatch to special holding areas, called ‘concentration camps’. Although comparisons with their Second World War German namesakes are grossly exaggerated and unfair (the British were not waging a policy of genocide), administration and public health in the camps were dreadful, and discipline harsh: of a total of 116,000 Boers confined, at least 28,000 died.

A second Canadian contingent arrived in South Africa in the period January-March 1900. The success of the Boers’ mounted commando tactics had persuaded British commanders that their enemy would best be countered by similar mobile mounted units. Thus, the new Canadian contingent consisted of the 1st and 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR). The former was renamed the Royal Canadian Dragoons (RCD) after its arrival, with the latter becoming the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles. In addition, the contingent included “C”, “D”, and “E” batteries of the Royal Canadian Field Artillery (RCFA), each with six 12-pounder field guns.

The core of the RCD‘s manpower derived from the regular army unit bearing that name; a large number of the CMRs came from the para-military North West Mounted Police (NWMP) from the future provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta. Except for very small postal, medical, and nursing contingents, all Canadian units sent subsequently to South Africa were mounted rifles.

Some of the second contingent joined Lord Roberts’s advance to Pretoria in May-June 1900 and, in May, “C” Battery of the RCFA participated in the long-awaited relief of General Robert Baden-Powell’s besieged garrison at Mafeking. For the most part, however, as the nature of the war changed from large set-piece battles to a cat-and-mouse struggle across the veldt, the new arrivals patrolled lines of communication, participated in search-and-destroy missions against Boer commandos, and removed Boers from their lands for transport to the dismal concentration camps.

One of these expeditions of 6-7 November 1900 resulted in the second-most famous Canadian engagement of the war. A large British-Canadian force headed southwards from the town of Belfast in search of a Boer commando known to be in the area. After reaching a farm called Leliefontein the British commander, fearing that he was dangerously overextended, decided to withdraw, leaving a detachment of the RCDs and a section of “D” battery, RCFA, with two 12-pounder guns, as a rear guard. The Boers mounted a massive assault against the Canadians, and made a determined effort to capture their guns. Outnumbered about three to one, the Canadians fought desperately. With Boer riflemen closing in on one gun, an already twice-wounded Lieutenant Richard Turner and a small detachment of Dragoons interposed themselves between it and the advancing Boers. Their fire killed the two Boer commanders, the assault lost momentum, and the Canadians were able to make good their escape. Three Dragoons, Lieutenants Turner and H.Z.C. Cockburn, and Sergeant E.J.G. Holland, were awarded the Victoria Cross, the largest number ever earned by Canadians for a single action except for Vimy Ridge in 1917.

Another unit sent to South Africa from Canada was Strathcona’s Horse. Completely financed by Donald A. Smith, Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, Canada’s High Commissioner in London, this was another force of mounted infantry. Raised in the Canadian West, it – like the Canadian Mounted Rifles – contained a large number of men from the ranks of the NWMP. Under the leadership of its charismatic, hard-riding, and hard-drinking commanding officer, former mounted police superintendent Sam Steele, the troops were “not just stereotypical rough-riders of the plains”, but also “a corps d’élite”. The Strathconas served in South Africa from April 1900 to January 1901; one of its members, Sergeant Arthur Richardson, earned a Victoria Cross at Wolve Spruit in July for rescuing a wounded comrade under intense enemy fire.

In March 1901, 1248 Canadians left for South Africa to serve with the South African Constabulary, a large British unit formed to help police the country after hostilities ceased. Many of them remained in South Africa years after the Treaty of Vereeniging ended the war in May 1902. In addition, Canada raised five more battalions of mounted rifles. The 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles, which arrived in January 1902, was the last Canadian unit to see action, at the battle of Harts River on 31 March. With 13 Canadians killed and 40 wounded, this was Canada’s bloodiest engagement of the war after Paardeberg. The 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th Canadian Mounted Rifles (2036 officers and men in all), arrived in South Africa in mid-June, after the Boer surrender.

A total of 7368 Canadians served in South Africa. Another 1004 served with the 3rd (Special Service) Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry, as garrison troops in Halifax, thus freeing up a British battalion for service in the war. Of the Canadians who went to South Africa, 89 were killed in action, 135 died of disease, and 252 were wounded. Although many of them may have embarked seeking high adventure, they found instead an oppressively hot and dry climate, and diseases of various sorts, which took a constant toll. Probably most were pleased to see the last of the country when their term of service expired.

Compared with the total British commitment in South Africa of about 450,000 men, Canada’s effort was a very small one. Still, Canadians were seen by themselves, and by others, to have done very well in South Africa, fully the equal in many respects of their British counterparts. As Lieutenant E.W.B. Morrison of the RCFA put it, “Canada’s soldiers compare favourably with the “reglars” …while they lack to some extent the barrack yard polish…they more than make up for it in spirit and dash and a certain air of self-reliant readiness to hold their own.” The Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry gained a large share of the credit for the victory at Paardeberg, while the Canadian Mounted Rifle units were among the best of their type in the British order of battle. Although largely citizen soldiers, Canadians returned from South Africa confident in their ability to function together in full-time and effective military formations. While it was the cause of the British Empire that had first inspired their participation, once in South Africa Canadians developed a profound sense of distinctiveness from their imperial counterparts that nourished feelings of national pride and a sense of independent military identity.

Fighting together in South Africa taught the Canadians a number of valuable lessons. Thereafter, militia training became more realistic, and discipline tighter. In addition, Engineers, Signals, Service, and Ordnance Corps, were added to the order of battle, laying the ” foundation of a modern army.” During the much larger and bloodier conflicts to come in the twentieth century, Canadian soldiers were to fully justify the reputation their forebears had gained in South Africa.

Further reading

- Kruger, Rayne, Good-Bye Dolly Gray: the Story of the Boer War, Philadelphia, J.P. Lippincott, 1960.

- Miller, Carman, Painting the Map Red: Canada and the South African War, 1899-1902, Montreal and Kingston, Canadian War Museum and McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993.

- Morrison, Lieutenant E.W.B., With the Guns to South Africa, Hamilton, Spectator Publishing Company, 1901.

- Morton, Desmond, The Canadian General: Sir William Otter, Toronto, Hakkert, 1974.

- Pakenham, Thomas, The Boer War, London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1979.

- Reid, Brian, Our Little Army in the Field: The Canadians in South Africa, 1899-1902, St. Catharines, Ontario, Vanwell Publishing, 1996.