From the series “Dispatches: Backgrounders in Canadian Military History”

Introduction

(Note that some of the content in this series is outdated and is under review.)

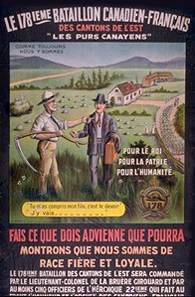

During the First World War, the Canadian government used posters as propaganda devices, for fund raising purposes and as a medium to encourage voluntary enlistment in the armed forces. Posters were an important form of mass communication in pre-radio days and hundreds existed during the war, some with print runs in the tens of thousands.

Because of Canada’s bilingual character, recruiting poster images and text reflected different cultural traditions, outlooks and sensibilities. Recruiting posters remain snapshots in time, helping historians understand the issues and moods of the past.

The French-Canadian recruiting posters on display in the Les Purs Canayens exhibit reflect Canada’s pressing demand for manpower during the First World War. They also indicate the underlying social, cultural and political strains which affected Canada’s war effort and influenced military policy. Most French-speaking Canadians did not support Canada’s overseas military commitments to the same degree as English speakers.

At the outbreak of war in August 1914, the Dominion of Canada was constitutionally a subordinate member of the British Empire. When Britain was at war, Canada was at war: no other legal option existed. Nevertheless, Ottawa determined the actual nature of Canada’s contribution to the war effort, not London.

When Canadians learned they were at war, huge flag-waving crowds expressing loyalty to the British Empire drowned out voices of caution or dissent. The war would be a moral crusade against militarism, tyranny, injustice, and barbarism. “There are no longer French Canadians and English Canadians,” claimed the Montreal newspaper, La Patrie, “Only one race now exists, united…in a common cause.” Even Henri Bourassa, politician, journalist, anti-imperialist, and guiding spirit of French-Canadian nationalism, at first cautiously supported the war effort. Few Canadians could have predicted at this time that their nation soon would become a major participant in the worst conflict the world had yet seen, or that the war would place enormous political and social strains on Canada.

Recruitment: Policy Versus Reality

The Conservative government of Prime Minister Robert Borden immediately offered Britain a contingent of troops for overseas service. Thousands of men enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), then assembling at Valcartier, Québec under the personal, if chaotic, supervision of Sam Hughes, the exuberant Minister of Militia and Defence. There was a surplus of volunteers and selection standards remained high; some men, in fact, were turned away. On October 3, a convoy of ships carrying nearly 33,000 Canadian troops departed for Britain. In December 1914, Borden announced solemnly that “there has not been, there will not be, compulsion or conscription”. To find whatever manpower might be necessary, Borden placed his faith in Canadians’ patriotic spirit.

Fully two-thirds of the men of the first contingent had been born in the British Isles. Most had settled in Canada in the 15-year period of massive immigration which had preceded the Great War. The same attachment to the Mother Country was less obvious among the Canadian born, especially French Canadians, of whom only about 1000 enlisted in the first contingent. At the time war was declared, only 10 percent of the population of Canada was British born. Yet, by the Armistice in 1918, nearly half of all Canadians who served during the war had been born in the British Isles. These statistics indicate that voluntary enlistments among the Canadian born were never equal to their proportion of the population.

Following the despatch of this first contingent, the Department of Militia and Defence delegated the task of recruiting to militia units across the country. This decentralized and more orderly system raised a total of 71 battalions — each of approximately 1000 men — for service overseas. Posters, which appeared in every conceivable public space, were an important part of this large recruiting effort. The poster text and images were usually designed and printed by the units themselves and tailored to local conditions and interests. Many of the posters on display are good examples of these.

Recruitment, however, was already tapering off in the fall of 1915. In October of that year, Ottawa bowed to the pressure of patriotic groups and allowed any community, civilian organization or leading citizen able to bear the expense to raise an infantry battalion for the CEF. Some of the new battalions were raised on the basis of ethnicity or religion, others promoted a common occupational or institutional affiliation or a shared social interest, such as membership in sporting clubs, as the basis of their organization. For example, Danish Canadians raised a battalion, two battalions recruited “Bantams,” men under 5 feet 2 inches tall, and one Winnipeg battalion was organized for men abstaining from alcohol. Up to October 1917 this “patriotic” recruiting yielded a further 124,000 recruits divided among 170 usually understrength infantry battalions.

In July 1915, with two contingents already overseas and more units forming, Ottawa set the authorized strength of the CEF at 150,000 men. Extremely heavy Canadian casualties that spring during the Second Battle of Ypres indicated that additional manpower would be required on an unprecedented scale. There would be no quick end to the fighting. In October, Borden increased Canada’s troop commitment to 250,000; by the new year, this had risen to 500,000. This was an almost unsustainable number on a voluntary basis from a population base of less than eight million. Within months, voluntary enlistments for Canadian infantry battalions slowed to a trickle.

Unemployment had been high in 1914-1915, and this perhaps had prompted the initially heavy flow of enlistments, especially from economically-troubled Western Canada. By 1916, the booming wartime industrial and agricultural economies combined to provide Canadians with other options and employers competed with recruiting officers for Canada’s available manpower. Those keen to volunteer had already done so; the rest would have to be convinced — or compelled.

By the end of 1916, the CEF‘s front-line units required 75,000 men annually just to replace losses, which were extremely heavy among the infantry; yet, only 2800 infantry volunteers enlisted from July 1916 to October 1917 and not a single infantry battalion raised through voluntary recruitment after July 1916 reached full strength.

French Canada and Recruitment

Following the nation-wide outbursts of patriotism in August 1914, French-Canadian support for the war began to decline. There existed among French Canadians a tradition of suspicion and even hostility towards the British Empire, and, while sympathetic to France, Britain’s ally, few French Canadians were willing to risk their lives in its defence either. After all, for over a century following the British conquest of New France in 1760, France showed no interest in the welfare of French Canadians. In North America, les Canadiens had survived and grown, remaining culturally vibrant without French support. By 1914, while an educated élite in French Canada professed some cultural affinity, most French Canadians did not identify with anti-clerical and scandal-ridden France.

When a French government propaganda mission toured Québec in 1918, Bourassa spoke for French Canada when he wrote of the irony of the French “trying to have us offer the kinds of sacrifices for France which France never thought of troubling itself with to defend French Canada”. In short, neither France nor Britain was “a mother country” retaining the allegiance of French Canadians. The “patriotic” call to arms rang hollow.

French Canadians’ language and culture seemed more seriously threatened within Canada than by the war in Europe. In 1912, Ontario passed Regulation 17, a bill severely limiting the availability of French-language schooling to the province’s French-speaking minority. French Canada viewed this gesture as a blatant attempt at assimilation, which it had resisted for generations. Bourassa, who by 1915 saw the war as serving Britain’s imperial interests, insisted that “the enemies of the French language, of French civilization in Canada are not the Boches [the Germans]…but the English-Canadian anglicizers…” Bourassa’s acerbic campaign against the “Prussians of Ontario” had a major impact on recruiting for “Britain’s” war. The Montreal daily, La Presse, judged Ontario’s unyielding Regulation 17 as the main reason for French-Canadian apathy. To English Canada’s calls for greater French-Canadian enrollment, Armand Lavergne, well-known nationaliste, replied: “Give us back our schools first!” Wartime appeals for unity and sacrifice came at an inopportune time.

French Canada’s views were reflected in low enrollment numbers. Yet, most Canadians of military age, notwithstanding language, did not volunteer. Those tied to the land, generations removed from European immigration, or married, volunteered the least. Significantly, these characteristics applied most often to French Canadians, although many rural English-Canadians were not enlisting either. If British immigrants are not counted, the respective contributions of French and English Canadians are more proportional than the raw data would suggest.

When the first contingent of the CEF sailed in October 1914, it contained a single organized French-speaking company (about 150 men). Sam Hughes at first refused to authorize any French-language units. The second contingent of over 20,000 men, despatched to Britain in early 1915, had a single French-speaking Québec battalion, the 22nd, later nicknamed the “Van Doos.” Besides this battalion, the CEF was almost entirely an English-language institution, hardly an inducement for a French-Canadian to volunteer. A mere 13 of 258 infantry battalions formed during the course of the war were raised in French Canada, and all struggled to attract and retain recruits. Those understrength French-speaking battalions which proceeded overseas after 1915 were invariably broken up to reinforce the 22nd and other units suffering severe infantry shortages.

Occasionally in 1915 and 1916, respected and battle-hardened officers of the 22nd would be assigned to newly-formed French-language battalions in the hope that a claim to some association with the famed “Van Doos” might encourage prospective enlistees. It rarely did. In June 1916, the 167th Battalion, recruiting in Québec City, even tried raffling an automobile to raise interest but only raised 144 men for service at the front with the 22nd. One interesting unit was the 163rd Battalion, raised in November 1915 by the noted nationaliste journalist and adventurer, Olivar Asselin, who insisted on enrolling only high-calibre men. Criticized by his nationaliste colleagues for enlisting, Asselin explained in the pamphlet, Pourquoi je m’enrôle that, far from being a hypocrite, he was helping to defend France and not the British Empire. Asselin nicknamed his unit “les poils-aux-pattes” [hairy paws] and adopted the porcupine as his regimental emblem, explaining that “qui s’y frotte s’y pique” [stung are those who come into contact with it]. The unit’s recruiting poster, on display in the exhibit, featured a soldier in French, not Canadian, uniform. Asselin’s considerable efforts to raise a high-quality French-language battalion were in vain: despite successful recruiting, the 163rd was despatched to Bermuda for garrison duty, where it languished. It, too, was eventually dismantled to reinforce the 22nd.

French Canada supplied approximately 15,000 volunteers during the war. Most came from the Montreal area, though Québec City, Western Québec and Eastern Ontario provided significant numbers. A precise total is difficult to establish since attestation papers did not require enlistees to indicate their mother tongue. Though French Canadians comprised nearly 30 percent of the Canadian population, they made up only about 4 percent of Canadian volunteers. Less than 5 percent of Quebec’s males of military age were enrolled in infantry battalions, compared to 14-15 percent in Western Canada and Ontario. Moreover, half of Quebec’s recruits were English Canadian and nearly half of French-Canadian volunteers came from provinces other than Québec. The result was an angry national debate concerning French Canada’s, and especially Québec’s, manpower contribution.

Conscription and its Aftermath

When Borden pledged in 1914 that there would be no conscription in Canada he also maintained that Canada would furnish whatever manpower was needed to help win the war. By the spring of 1917, these two policies had become irreconcilable. Voluntary enrollment was no longer producing the reinforcements necessary to maintain Canada’s commitment in the field where the CEF had suffered appalling casualties. Worse was yet to come.

In May 1917, Borden visited Vimy Ridge in the immediate aftermath of that costly Canadian victory. Moved by the hardships endured by the troops and proud of their battlefield achievements, on May 18, upon his return to Canada, Borden announced that “all citizens are liable for the defence of their country and I conceive that the battle for Canadian liberty and autonomy is being fought on the plains of France and Belgium.” The government began drafting the Military Service Act.

Many English Canadians hailed the step as a military necessity, but also as a means of forcing French Canada to augment its low enlistment rate. Saturday Night magazine insisted that “it is certainly not the intention of English Canada to stand idly by and see itself bled white of men in order that the Québec shirker may sidestep his responsibilities.” English Canada hated Bourassa as much as the German Kaiser. There was little sympathy for French Canadians and little understanding of the demographic, cultural or historical factors which might have dissuaded them from enlisting.

The Military Service Act became law on August 28. Former prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier claimed the measure “has in it the seeds of discord and disunion”. He was correct; anti-conscription demonstrations occurred regularly in Montreal in the summer of 1917. Angry crowds broke office windows at the pro-conscription Montreal newspaper, The Gazette. The home of Lord Atholstan, proprietor of the equally pro-conscription Montreal Daily Star, was dynamited earlier that month although he escaped unharmed. Recruiting officers in various parts of Québec made themselves scarce for fear of their lives. Crowds chanted: “Nous en avons assez de l’Union Jack!”

The political truce which had prevented a wartime election ended. Parliament was dissolved in October 1917 and pro-conscription Liberals joined Borden’s Conservatives to form a Union Government, something of a misnomer since its founding was the result of national disunity. Some labour groups, most farmers and many Canadians of non-British origin were also firmly opposed to conscription. J.C. Watters, the president of the Trades and Labour Congress threatened that if conscription passed, Canadian workers “would lay down… tools and refuse to work”.

The ensuing December 17 “conscription” election was by far the most bitterly-contested and linguistically-divisive in Canadian history. In the end, the Unionists won 153 seats against the Laurier Liberals’ 82, including 62 obtained in Québec, but the popular vote was less than 100,000 in favour of the Unionists. The result was profound alienation in French Canada. Conscription was considered the result of the English-language majority imposing its views over a French-language minority on an issue of life and death. Conceptions of Canada and definitions of patriotism had never been further apart. Canadian national unity had never seemed so fragile.

The first group of conscripts were called in January 1918. There were slightly more than 400,000 Class I registrants; that is, unmarried and childless males aged 20-34. Nationally, almost 94 percent of these men applied for various exemptions from service (98 percent in Québec) and the appeal boards established to review these cases granted nearly 87 percent of their requests (91 percent in Québec). Some 28,000 others (18,000 in Québec) simply defaulted and went into hiding to avoid arrest by military or civilian police. Conscription was unpopular among those called, regardless of region, occupation or ethnicity.

The tension in Québec was palpable. At the end of March 1918 a mob destroyed the offices of the Military Service Registry in Québec City. Conscript troops were rushed from Toronto and on April 1 they opened fire with machine guns on a threatening crowd, killing four demonstrators and wounding dozens of others. The extent of the violence shocked the country. Religious leaders and civic authorities successfully appealed for calm. The rioting stopped, but the bitter memories would linger for decades.

Of the 620,000 men who served in the CEF, about 108,000 were conscripts. Fewer than 48,000 of these proceeded overseas and, before the war ended in November 1918, only 24,000 actually served at the front. Although all of the conscripts would have been urgently needed at the front if the war had continued into 1919, as expected, conscription hardly seemed worth the effort given the severity of the national disunity it caused. In the postwar period, French-Canadian nationalistes would point to the conscription crisis as evidence of the impossibility of reconciling the views of French and English speakers in Canada. The events of 1917-1918 forced the government of William Lyon Mackenzie King to tread warily over the same issue during the Second World War.

Further reading

- Robert Craig Brown; Donald Loveridge, Unrequited Faith: Recruiting the CEF 1914-1918, Revue Internationale d’Histoire Militaire, No. 51, 1982.

- Marc H. Choko, Canadian War Posters, Méridien, Montreal, 1994.

- Gérard Filteau, Le Québec, le Canada et la guerre 1914-1918, L’aurore, Montréal, 1977.

- Jean-Pierre Gagnon, Le 22e Bataillon, Les Presses de l’Université Laval en collaboration avec le ministère de la Défense nationale et le Centre d’édition du gouvernement du Canada, Ottawa et Québec, 1986.

- J.L. Granatstein and J.M. Hitsman, Broken Promises: A History of Conscription in Canada, Oxford University Press, Toronto, 1977.

- Desmond Morton and J.L. Granatstein, Marching to Armageddon, Lester and Orpen Dennys, Toronto, 1989.

- Desmond Morton, When Your Number’s Up, Random House, Toronto, 1993.

- G.W.L. Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919, Ottawa, Queen’s Printer, 1964.