| Sculpture

Haida sculptures range from 20-metre (65-foot) tall totem poles to the equally complex carved handles of horn spoons. This ability to express artistic concepts over a range of sizes and forms has attracted the admiration of art aficionados worldwide over the past two centuries.

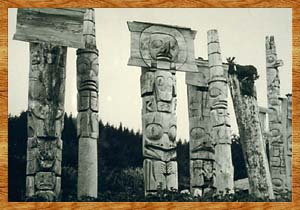

The earliest known Haida sculptures are from cave sites or remote graves of shaman that date from the mid-eighteenth century. The oldest carved poles are undoubtedly shaman grave posts, some of which are late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. They portray primarily human figures, whereas the monumental poles standing in the villages display crests and supernatural beings from mythology. The earliest surviving poles include triple mortuary posts circa 1820 from Kiusta and a large house pole circa 1840 from Hiellan village. On these four poles, the figures are very large and few in number, with many small faces appearing at the joints, eyes and ears.

The oldest burial chest is from the Gust Island burial cave, while a slightly later example from an eighteenth-century mortuary at Kiusta is now in the Royal British Columbia Museum. In both examples, the eye forms are very elongated, with slits in the pupils. Another early piece is a sea lion-shaped bowl that is characteristic of the eighteenth-century pieces collected by early explorers.

The majority of Haida carvings created during the last half of the nineteenth century belong to the classic style. Facial features such as eyes, ears, nostrils and lips are very large, and occupy about the same space as the forehead, cheeks and jaw. This gives the animal or bird forms a youthful or even naive look that viewers find appealing. The formal symmetry of the crest art also provides a serenity and charm akin to Egyptian art. Smaller sculptures such as masks and frontlets range from the mystic to the frightening, and occasionally the comical.

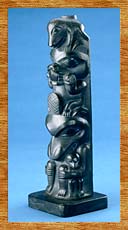

Following the tragic depopulation of the late 1860s due to epidemics and the deculturation of the survivors by Indian agents and missionaries in the 1870s and 1880s, the monumental sculptural tradition was abandoned. Carvers miniaturized their production into models of houses and poles, tailoring their art to the tourist market. Few new artists were trained, and eventually the canons and tenets of the distinctive Haida style were lost. Those traditions were rediscovered by the current generation of artists who learned by studying models on dusty museum shelves. Following the tragic depopulation of the late 1860s due to epidemics and the deculturation of the survivors by Indian agents and missionaries in the 1870s and 1880s, the monumental sculptural tradition was abandoned. Carvers miniaturized their production into models of houses and poles, tailoring their art to the tourist market. Few new artists were trained, and eventually the canons and tenets of the distinctive Haida style were lost. Those traditions were rediscovered by the current generation of artists who learned by studying models on dusty museum shelves.

|