Albert Edward Albert Edward

Edenshaw Edenshaw

John Robson John Robson

Charles Charles

Edenshaw Edenshaw

|

Artists of the Golden Age

The golden age of Haida art lasted half a century, beginning in the 1850s when new markets opened in Victoria and elsewhere that stimulated both greater production and the development of new art forms, until the collapse of the Haida population at the beginning of the twentieth century. During this period, large objects were replaced by smaller replicas that could easily be taken home by tourists as mementoes of their visits to the Northwest Coast. It was a golden age because there was not only a great number of Haida artists who were well trained in their traditional style yet felt free to innovate and create new expressions of their rich heritage but also because there was a large and eager market for their work.

These Haida artists successfully made the transition to creating pieces for another cultural milieu where having an identifiable style was essential in the marketplace. Even so, signing their work was not an accepted practice, and many artists resisted it, preferring to express themselves through subtle variations on traditional style. This has resulted in endless speculation among scholars who pen articles with titles like "Will the Real Charles Edenshaw Please Stand Up?". At least one thesis and several articles have been written on Charles Edenshaw, of which the best are by Bill Holm and Alan Hoover. The work of carver Tom Price also has been the subject of study. Bill Holm originally defined one body of work as that of the Masset artist Gwaitilth, but later found evidence that it was by another Masset artist named Simeon Stiltla. Marius Barbeau published short studies of many Masset and Skidegate artists of a later period.

The momentum of the golden age of Haida art came to an end as lineage groups broke down into separate family units and Christianization turned Haida myths into the equivalent of fairy tales. Argillite carvings continued to be sold through intermediaries to tourist shops in Victoria and Vancouver, but as tourist values took over the market, argillite poles were priced by the inch, and the pride of individual craftsmanship virtually disappeared.

After the last two artists of the golden age died, Charles Edenshaw in 1920 and John Cross in 1939, Rufus Moody and a number of others did what they could to bridge the gap until a new generation of sophisticated artists, many of them trained in art schools, rekindled the flame that led to the renaissance of Haida art beginning in the 1950s and 1960s.

|

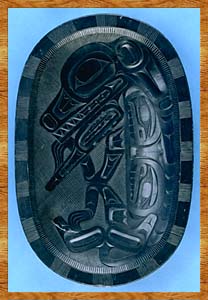

An oval argillite platter with a very compact design of a Wasgo, or Sea Wolf. It has both legs and fins, and a long wolflike tail curves over its back. The inverted crescent-shaped slits in the eye forms and other details identify it as the work of the Skidegate carver Tom Price (Chief Ninstints).

Acquired before 1899 for the A. Aaronson collection.

CMC VII-B-760 (S82-265) |

|

Bill Reid Bill Reid

Robert Davidson Robert Davidson

Jim Hart Jim Hart

The Next The Next

Generation Generation

|

Death and Rebirth of the Raven

The world is highly sensible of the loss incurred when a species of bird or fish is lost to extinction, yet we are less concerned with the loss of a unique culture. Perhaps, like the survivors of the Black Plague, we celebrate our own survival while ignoring the destruction of others. The age of colonization was just such a plague in the cultural history of mankind. Countless thousands of cultures that had survived and thrived for millennia in various pockets of the earth's habitats suddenly were swamped by warfare and pestilence such as they had never known before. The Haida stand as an example of that physical and cultural decimation.

When the first European sailor spotted the shores of Haida Gwaii in 1774, the Haida population stood at close to twelve thousand, counting both the Prince of Wales archipelago and Haida Gwaii (the Queen Charlotte Islands). By the turn of the century, that population had been dramatically reduced to less than five hundred. Most indigenous peoples in the New World lost 90 per cent of their population to their collision with Europeans. The Haida lost more than 95 per cent.

When I began research on Haida Gwaii in 1966, the number of fluent Haida speakers was estimated at less than forty. Today, programs in the schools have helped those figures to begin to grow, but it still remains to be seen if the Haida can achieve what the Maori of New Zealand have done with their concept of "language nests" (interactive groups) as brooders of indigenous language. The isolation of the Maori from other large populations and their current position as more than 10 per cent of the population of New Zealand provide safer ground for optimism than for the Haida, overwhelmed as they are by English speakers. Even on their own islands they are a minority of the population, although this may change in the next few decades.

Robert Davidson and Raven Bringing Light to the World |

The renaissance of Haida culture, however, is attributable to a growing number of artists. Bill Holm notes that the formline style of Northwest Coast art is calligraphic in principle: that is, there is an implicit grammar at play in each work that determines the message of the piece. In a wonderful interplay between anthropologists, art historians and the new generation of Haida artists, this grammar has been reviewed and extended.

|