|

Secret societies and their performances began to disappear with the arrival of the missionaries in the mid-1870s. A photograph documenting the participants in the last secret society dances at Skidegate in the 1880s shows some of the young women wearing masks while others wear frontlets or have painted their faces.

|

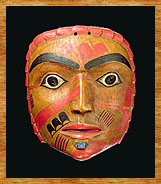

A mask of a young woman wearing a small labret of abalone shell and with face painting. The red scalelike carving around the rim is an unusual feature.

Collected on Haida Gwaii in 1879 by Israel W. Powell.

CMC VII-B-928a (S85-3284) |

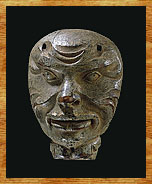

Among the Haida, masks were used mostly by members of the secret societies. Secret society dances frequently used both masks and puppets to represent wild spirits of the woods, which the Haida called gagiid. They are distinguished by an emaciated or wrinkled face and grimacing mouth, and are often blue-green in colour, to indicate that they portray a person who has narrowly escaped drowning and whose flesh has gone cold from long exposure in cold water.

|

The head of a gagiid doll used in secret society dances. The cloth body as well as the wooden hands and feet have been lost.

Collected at Masset before 1900 by Charles F. Newcombe.

CMC VII-B-526 (S94-6728) |

Like their Tsimshian neighbours, the Haida also employed masks in potlatch performances to illustrate the spirit beings (geni loci) encountered by their ancestors. Unfortunately, much less is known about such supernatural being masks among the Haida than about the nox nox (or supernatural spirit) masks of the Tsimshian, who to this day have maintained their traditions in some interior villages.

The influence of the tourist market on Haida mask-making is difficult to evaluate. After the 1840s, masks and argillite carvings were the items most sought after by seamen, traders and tourists, and probably several thousand Haida masks are held in private and museum collections around the world. Deciding which masks were made for traditional use rather than for sale is largely a matter of judgement. Indicators of actual use include signs of wear on the leather ties and interior surface, the functionality of the eyeholes, the allowance for facial fit for wearing, evidence of attachments of headcloths or animal fur that was stripped off before sale, and traces of glue and down or cedar bark. The opposite factors such as no means for attaching the mask to the wearer's head, no preparation of the interior to avoid rubbing the wearer's nose and no functional eyeholes indicate that a mask was made for tourists.

Famous artists like Simeon Stiltla and Charles Edenshaw are known to have made masks for ceremonial use. One such example is the elaborate transformation mask by Charles Edenshaw now in the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University.

|