|

|

|

|

|

|

Northwestern Palaeo-Arctic Culture

(Précis, Chapter 3)

The earliest securely dated

archaeological sites in eastern and western Beringia involving

Yukon/Alaska and eastern Siberia, respectively, fall between 10,000

and 14,000 B.P.

(Morlan 1987). For 10,000 to

15,000 years prior to 14,000 B.P. a harsh Arctic environment existed

and it has been suggested that Beringia may have been uninhabitable

(Fladmark 1983: 22-23;

Schweger et al. 1982: 439).

Between 10,000 and 8,000 B.C. and probably earlier, an Asiatic-derived

Upper Palaeolithic culture spread across much of the unglaciated

territory of Beringia in Alaska and the Yukon. Originally called the

American Palaeo-Arctic tradition

(Anderson 1970) the name has

been changed in this work to reflect more accurately the culture's

geographical position in the Western Hemisphere. Technological

similarities between Northwestern Palaeo-Arctic culture and Siberian

assemblages have encouraged even more inclusive designations such as

the Siberian-American Paleo-Arctic tradition

(Dumond 1977) and the Beringian

tradition

(West 1981). Also in common use

is the term Denali complex (West 1967).

Possessing a technology characterized by specially prepared microblade

cores, microblades, burins, and few bifacial tools, Northwestern

Palaeo-Arctic culture may be regarded as the eastern expression of a

circumpolar Eurasian technological tradition

(Larsen 1968: 71-75). Its close

relationship to Siberian cultures

(Anderson 1980;

Mochanov 1978;

Powers 1973) should not be

surprising. Beringia was more a part of Asia than America, representing

an extension of the Asiatic steppe tundra to the glacial ice of the

eastern Yukon and southern Alaska. Most excavated Northwestern

Palaeo-Arctic sites are in Alaska where the earliest evidence dates

around 10,500 B.P. although there are a number of earlier dates whose

veracity is questioned

(Anderson 1984). The earliest

site in the northern Yukon to produce microblades and burins has been

estimated to have a minimum date of 10,000 B.P. and, on the basis of a

range of archaeological and environmental evidence, could be earlier

than 13,500 B.P.

(Cinq-Mars 1979;

1990). These age estimates

pertain only to the Northwestern Palaeo-Arctic culture materials and

not to potentially earlier evidence of human activity at the site.

|

|

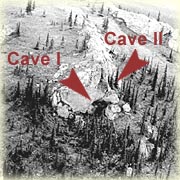

Aerial View of the Bluefish Caves Site,

Yukon Territory

|

|

The deposits in the Bluefish Caves

site are unique in northwestern North America in that they

constitute 25,000 years of in place accumulation. In addition to

the archaeological evidence is the sedimentological record, the

palynological evidence left by tree pollens as well as actual plant

fragments, and the palaeontological remains. All of these data sets

are extremely relevant to the archaeological evidence. Allowing for

some disturbance of the primary deposits, evidence of Northwestern

Palaeo-Arctic culture falls between 10,000 and 13,500 B.P.

(Cinq-Mars 1990: 20-21).

Earlier but more controversial evidence occurs in lower levels.

Whether one accepts or rejects these early dates for microblades and

burins depend upon one's assessment of the extent of post-depositional

disturbance at the site and the association of the stone tools with the

Late Pleistocene environmental evidence. The two arrows in the lower

left hand corner of the picture indicate the mouths of Cave 1 and

Cave 2.

(Reproduced from Cinq-Mars

1979: Figure 2 with the

permission of Jacques Cinq-Mars, Archaeological Survey of Canada,

Canadian Museum of Civilization)

|

|

|

Cultural continuity from Northwestern Palaeo-Arctic culture in Alaska

has been traced to approximately 6,000 B.C. with events up to 4,600

B.C. being poorly understood

(Anderson 1984). By the end

of Period I (8,000 B.C.) microblade technology had spread south into

southeastern Alaska

(Ackerman 1980), down the

Pacific coast, and possibly eastward along the Yukon coast. Given

the diversity of environmental and physiographic zones occupied the

descendants of the Northwestern Palaeo-Arctic culture appear to have

possessed both maritime and interior adaptations

(Fladmark 1983).

While Northwestern Palaeo-Arctic culture has been interpreted as the

intrusion of a new Asiatic population

(Greenberg et al. 1986)

which absorbed an earlier Nenana-Chindadn population and its derivatives,

it more likely reflects the diffusion of microblade technology into

Beringia and its adoption by earlier people

(Gotthardt 1990: 267). This

scenario assumes that pre-microblade people actually settled eastern

Beringia first and that the Upper Palaeolithic derived Palaeo-Indian

and Northwestern Palaeo-Arctic cultures are not technologically and

biologically related; an assumption that is far from being

demonstrated. It is inappropriate to view the migratory behaviour of

these small bands of northern hunters as similar to the mass movements

of later Asiatic pastoralists. Their territorial movements were not

only generational and, therefore, incremental

(Morlan 1987: 267-268) but would

have taken place within a far-flung communication network

(Morlan and Cinq-Mars 1982).

Under such circumstances the spread of innovative technologies could

potentially be quite rapid. Migration into Beringia was more likely a

matter of 'dribbles' rather than 'waves' and would have involved many

back and forth movements rather than single-minded eastward thrusts.

The chipped stone technologies of Palaeo-Indian culture and Northwestern

Palaeo-Arctic culture appear to be essentially the same except for the

microblade industry of the latter. Even this qualification is in doubt

if the association of fluted points and microblades at the Palaeo-Indian

Putu site in northern Alaska proves to be valid

(Alexander 1987). Others,

however, have argued that the two assemblages are technologically

distinct (Dixon 1985: 54) and

unrelated (Haynes 1982). Beyond

the issue of the technological relationship between the Nenana complex

and the related Chindadn complex

(McKenna and Cook 1968) and

Northwestern Palaeo-Arctic culture is the evidence that both cultures

occasionally occupied the same sites

(Powers and Hoffecker 1989)

suggesting a similar way of life. Further, genetically based discrete

human cranial attributes can be interpreted as evidence of a biological

relationship between these two early populations. Contrary to the

currently popular view of two migrations involving a culture with a

bifacial industry followed by a culture with a microblade industry,

the evidence from the Diuktai culture in Siberia and the early evidence

from the Bluefish Caves site in eastern Beringia does not support the

technological distinctiveness of the two industries nor the chronological

priority of one over the other. The recent discovery of microblades in a

11,700 B.P. level of the Swan Point site

(Mason 1993) reinforces the above.

In addition, bifacial tools and microblades are more often than not

found together

(Morlan 1987). Any assessment of

the archaeological evidence from Beringia at this time must be cautious

given its impoverished nature. The limited and equivocal nature of the

evidence is undoubtedly responsible for current divergent archaeological

opinion.

|

|

|

|

|