|

Yacht Builders - Early Adopters

ecause of the highly competitive

nature of yacht racing, whether at the club, national, or international

levels, the yachting fraternity almost zealously embraces advances in

small craft design and technology. Yacht builders and owners rush to

incorporate new equipment, materials, and ideas. They act as enthusiastic,

unofficial research and development partners. Commercial- or fishing-boat

builders and operators are slower to adopt these same advantages. They use

their vessels for business and must maintain complete reliability and trust.

New fastenings, such as ring nails; new shapes like the deep Vee or planing

hulls; or, in earlier times, the gaff-free Bermuda or the Marconi sailing

rigs, were all found in recreational craft before fishing vessels. Not least

among these technical changes was the adoption of glass reinforced plastic

(GRP), more commonly called "fibreglass". The pleasure craft fraternity

embraced fibreglass for sail and power boats in the late 1940s, and almost

universally converted to the new material on both sides of the Atlantic by

the mid-1950s. ecause of the highly competitive

nature of yacht racing, whether at the club, national, or international

levels, the yachting fraternity almost zealously embraces advances in

small craft design and technology. Yacht builders and owners rush to

incorporate new equipment, materials, and ideas. They act as enthusiastic,

unofficial research and development partners. Commercial- or fishing-boat

builders and operators are slower to adopt these same advantages. They use

their vessels for business and must maintain complete reliability and trust.

New fastenings, such as ring nails; new shapes like the deep Vee or planing

hulls; or, in earlier times, the gaff-free Bermuda or the Marconi sailing

rigs, were all found in recreational craft before fishing vessels. Not least

among these technical changes was the adoption of glass reinforced plastic

(GRP), more commonly called "fibreglass". The pleasure craft fraternity

embraced fibreglass for sail and power boats in the late 1940s, and almost

universally converted to the new material on both sides of the Atlantic by

the mid-1950s.

|

|

Colourful Cape Islander

Gale, a classic Cape Island boat, at rest for the winter near Chester

Basin, Nova Scotia. This boat was built at Vogler's Cove, Nova Scotia

in 1964, and her bright colours are typical of the genre.

(Courtesy: David Walker)

|

|

New Materials in the Fishery

n 1961, Nova Scotia started to

explore and promote the advantages of the new material in the fishery.

The Nova Scotia Department of Industrial Development commissioned the

building of a fibreglass inshore fishing boat. A contract was awarded to

the Atlantic Bridge Company of Lunenburg. The new Cape Island style boat

was designed by William Hines of the Department of Fisheries and was

christened Cape Islander when it was completed in 1962. The Nova Scotia

Department of Fisheries demonstrated the boat throughout the inshore

fishery, allowing fishermen to use the vessel in selected areas, under

varied conditions, and using various fishing technologies. n 1961, Nova Scotia started to

explore and promote the advantages of the new material in the fishery.

The Nova Scotia Department of Industrial Development commissioned the

building of a fibreglass inshore fishing boat. A contract was awarded to

the Atlantic Bridge Company of Lunenburg. The new Cape Island style boat

was designed by William Hines of the Department of Fisheries and was

christened Cape Islander when it was completed in 1962. The Nova Scotia

Department of Fisheries demonstrated the boat throughout the inshore

fishery, allowing fishermen to use the vessel in selected areas, under

varied conditions, and using various fishing technologies.

The vessel was not an instant success despite the benefits of the

homogenous leak-free hull, low maintenance costs, and other apparent

advantages. It seems the tradition-minded fishermen were unwilling to

accept the new material. Some said it made alterations to the vessel

difficult to achieve, while others claimed the material was too rigid

and too hard on the legs of men spending longs hours at sea. After some

years as a trial-horse, Cape Islander was retired to the government-owned

Liscomb Lodge for use as a pleasure boat by tourists who wanted to go

fishing. She has since been retired and can be seen in the collection

of the Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic in Lunenburg.

|

|

Fibreglass

ibreglass boat hulls are built

within a mould just as a jelly is moulded. First a full-sized hull,

called a plug, must be built in the exact form and shape of the desired

finished product. Since the plug is disposable, it can be built from a

variety of materials. When completed, the important exterior surface of the

plug is finished to the desired standard. It is covered with a coating of a

wax-like release agent and a series of layers of fibreglass cloth and

fibreglass matt, a less expensive felt-like material. Each layer is

impregnated with a synthetic polymer resin that cures and hardens. When the

desired thickness is achieved, the exterior of the mould is reinforced and

made rigid and self-supporting. It is then divided at the centreline from

the stemhead to transom cap. The mould is taken apart, and the plug is

removed and discarded. The edges of the division are reinforced to make

them remountable. A boat can now be built within the connected mould after

waxing the interior of the mould, starting with a gel coat. The gel coat

will form the exterior finish of the new hull. After the successive layers

have been built up again and the chemicals have cured, the mould is

separated, and the new hull removed for finishing. ibreglass boat hulls are built

within a mould just as a jelly is moulded. First a full-sized hull,

called a plug, must be built in the exact form and shape of the desired

finished product. Since the plug is disposable, it can be built from a

variety of materials. When completed, the important exterior surface of the

plug is finished to the desired standard. It is covered with a coating of a

wax-like release agent and a series of layers of fibreglass cloth and

fibreglass matt, a less expensive felt-like material. Each layer is

impregnated with a synthetic polymer resin that cures and hardens. When the

desired thickness is achieved, the exterior of the mould is reinforced and

made rigid and self-supporting. It is then divided at the centreline from

the stemhead to transom cap. The mould is taken apart, and the plug is

removed and discarded. The edges of the division are reinforced to make

them remountable. A boat can now be built within the connected mould after

waxing the interior of the mould, starting with a gel coat. The gel coat

will form the exterior finish of the new hull. After the successive layers

have been built up again and the chemicals have cured, the mould is

separated, and the new hull removed for finishing.

|

|

Fibreglass Boatyard Workers

Fibreglass boatyard workers rolling resin into fibreglass matt to remove

bubbles and to impregnate the material thoroughly.

(Courtesy: David Walker)

|

|

A newer and more efficient method of producing hulls has almost universally

replaced the hand lay-up of successive layers of impregnated fibreglass

cloth and matt. Materials are now sprayed into the interior of the mould

with a special gun that combines the resin and chopped strands of glass

fibres. Sometimes a combination of the layer and spray methods is used.

|

|

Fibreglass and Wood

ibreglass boatbuilding is

completely different from traditional wooden boatbuilding because the

materials are completely different. Natural wood has been replaced with

oil-based chemicals and mineral-based glass. There is no direct comparison

between the materials, just as there is no direct comparison between the

finished products. While they may look the same, the wooden boat is built

from scores of interconnected components skillfully assembled by

experienced hands from a carefully selected combination of woods,

fastenings and protective materials. In contrast, the fibreglass hull is

a completely homogenous entity, with no fastenings, openings or transitions

throughout the structure. This means that maintenance is much reduced on the

boats when they are new, although atmospheric elements and sun degrade their

components in time. ibreglass boatbuilding is

completely different from traditional wooden boatbuilding because the

materials are completely different. Natural wood has been replaced with

oil-based chemicals and mineral-based glass. There is no direct comparison

between the materials, just as there is no direct comparison between the

finished products. While they may look the same, the wooden boat is built

from scores of interconnected components skillfully assembled by

experienced hands from a carefully selected combination of woods,

fastenings and protective materials. In contrast, the fibreglass hull is

a completely homogenous entity, with no fastenings, openings or transitions

throughout the structure. This means that maintenance is much reduced on the

boats when they are new, although atmospheric elements and sun degrade their

components in time.

The choice lies between a high-maintenance, traditional, reliable product

and a low-maintenance, longer-lasting boat that most fishermen found more

acceptable despite the fact it was less comfortable on the water. The

homogenous hull is more rigid and does not "give" and flex with the sea

as wooden craft do. In other words, fibreglass boats are less comfortable,

but older fishermen who appreciated the wooden boats are more aware of

this discomfort than younger men who have totally embraced the new

technology.

|

|

Construction Details of a Wooden Boat

The interior of part of a derelict clinker-planked hull, showing the rusted

clench nails which hold the edges of the planks together and attach the

frames to the planking.

(Courtesy: David Walker)

|

|

Commercial Production of Fibreglass Boats Begins

fter 1962, almost a decade

passed before anyone in Nova Scotia considered building fibreglass boats

commercially. Reginald Ross of Clark's Harbour was a grandson and son of

wooden-boat builders in Clark's Harbour. He launched his first fibreglass

Cape Islander in 1971 and christened her Enterprises. She was 40 feet

long overall, just 8 percent longer than Atlantic Bridge Company's Cape

Islander, but almost 20 percent wider, illustrating the continuing trend

in Cape Island boat design. fter 1962, almost a decade

passed before anyone in Nova Scotia considered building fibreglass boats

commercially. Reginald Ross of Clark's Harbour was a grandson and son of

wooden-boat builders in Clark's Harbour. He launched his first fibreglass

Cape Islander in 1971 and christened her Enterprises. She was 40 feet

long overall, just 8 percent longer than Atlantic Bridge Company's Cape

Islander, but almost 20 percent wider, illustrating the continuing trend

in Cape Island boat design.

Ross built fibreglass fishing boats in quantity in the old Vimy movie

theatre in Clark's Harbour which had been converted for the purpose.

Notably, he hired two local women for part of his production staff. His

first fibreglass boats were small, open-hulled craft, larger but similar

to regional mossing boats. They were fitted with either outboard or

small inboard engines. The small craft were forerunners of larger

vessels, and when they were well received, Ross began to design their

successor. Unlike traditional builders, he drew his design on paper. He

then discussed his plans and the proposed idea with Ernest Atkinson. The

plans of Enterprises can be seen in the Achelaus Smith Museum,

Centreville, Cape Sable Island.

It is not known how Ross built his plug, but, in most cases, a plug was

built like a boat with a supremely well-finished exterior. The plans were

expanded to full size on the floor of the mould loft, and station moulds,

or templates, were built. The templates were erected on a strong,

keel-like back and planked over. There was no framing because the plug

had only to be strong enough to be self-supporting.

Enterprises generated much local interest and, though the new fibreglass

boats were much more expensive than their wooden counterparts, fourteen

examples were built and sold from that first Cape Island hull mould.

Ross' health unfortunately deteriorated, and he died prematurely. The

doors of J.D. Ross Enterprises, the island's first fibreglass boat shop,

closed forever in the mid 1970s.

Reginald Ross had done what the government had not been able to do, and

interest in fibreglass Cape Islander boats rapidly increased. Hulls were

soon being built in Dartmouth, and elsewhere in the province. Freebert

Atkinson began finishing bare fibreglass hulls, following a mainly

shipwright or carpentry process, but using fibreglass cloth and polyester

resin to connect and protect the wooden portions of the structure.

Freebert had gained enough experience by 1977 to start his own fibreglass

boatbuilding shop. He built the hulls and also finished them, but, as his

business increased, he concentrated on moulding hulls for other builders.

|

|

Modern Fibreglass Cape Island Boats

Part of the Wedgeport, Yarmouth County fleet of modern fibreglass Cape

Island boats. Note the close similarity among the characteristic high,

straight bows.

(Courtesy: David Walker)

|

|

The rapid acceptance of fibreglass soon eclipsed the wooden boatbuilding

industry. Like Freebert Atkinson, a few wooden boatbuilders retrained

and began manufacturing boats in the new and strange chemical materials.

They made a leap into a technology that was not an adaptation of the old,

but a completely different method of building. Those too slow to make the

transition were soon confronted with empty order books, and they quietly

closed their doors. Occasionally, traditionally minded fishermen decided

to stick with the much-trusted wooden craft and ordered new ones, but

faith in tradition was not enough to sustain the old industry.

A parallel business developed at about the same time, and for a few years

combined the old and new boatbuilding technologies. It was discovered

that a covering of fibreglass cloth and resin over the outside of a

wooden hull could give an old boat extended life, as well as lower

maintenance costs. This enabled less affluent fishermen to obtain some

of the benefits of a fibreglass boat at a much lower cost.

|

|

Sterns of Modern Fibreglass

Cape Island Boats

The sterns of the same 'raft' of Cape Island boats in Wedgeport.

(Courtesy: David Walker)

|

|

The large, open, working cockpits are now exposed to the transoms, as the

larger hulls allow the compact hydraulic steering gears to be fitted

beneath the soles. The small deck shelters have now been totally enclosed

with sliding doors to make a comfortable, warm, and weathertight

wheelhouse.

|

|

Fibreglass Boatbuilding Dominates

ibreglass boatbuilding expanded

throughout the province to supply all the requirements for inshore fishing

boats. Builders could be found in every area, but the heaviest concentration

of fibreglass boat shops was to be found on Cape Sable Island where numbers

rose to the extent that chemical and other suppliers were prompted to

establish warehouses there. The new production process meant that operators

had to be trained, and the trend started by Reginald Ross continued: builders

employed increasing numbers of women. They were found in almost every boat

shop, a place where women formerly had rarely been seen, and they were

engaged in boat production. Before the adoption of fibreglass, women

occasionally helped their husbands with the building of wooden boats. More

frequently, they were found keeping the books or doing the paperwork for the

small business. Now they actively moulded hulls - creating the boat. ibreglass boatbuilding expanded

throughout the province to supply all the requirements for inshore fishing

boats. Builders could be found in every area, but the heaviest concentration

of fibreglass boat shops was to be found on Cape Sable Island where numbers

rose to the extent that chemical and other suppliers were prompted to

establish warehouses there. The new production process meant that operators

had to be trained, and the trend started by Reginald Ross continued: builders

employed increasing numbers of women. They were found in almost every boat

shop, a place where women formerly had rarely been seen, and they were

engaged in boat production. Before the adoption of fibreglass, women

occasionally helped their husbands with the building of wooden boats. More

frequently, they were found keeping the books or doing the paperwork for the

small business. Now they actively moulded hulls - creating the boat.

The new material has enabled progressive builders to alter hull shapes and

make changes that were prohibitively expensive or impossible when using wood.

At least one innovative builder devised methods of constructing various sizes

of fibreglass hulls within one convertible mould. Perhaps more significantly,

traditional Cape Island hull shapes have changed only slightly since

fibreglass has been introduced. They are wider, deeper, and have greater

displacement, but essentially all this is done using the basic hull shape that

has remained virtually unchanged for 60 years. The single, most constant

characteristic is the flat aft run of the lines which has endured like a

pedigree from the early power-boat hulls of Atkinson, Kenney and their

followers.

These new hulls are virtually unrecognisable today, however, because they

are hidden under modern enclosed wheelhouses, atop raised forecastles without

cuddies. Some have extended hull platforms for extra capacity without

breaking construction size rules; others have insulated holds under

watertight decks that in turn allow open transoms. With sword-fishing towers

and pulpits at the end of extended bowsprits, some new craft are almost

completely new designs. But their owners and builders still cling proudly to

the "Cape Island Boat" as their title and heritage.

Today fibreglass Cape Island boats completely dominate the inshore fishery.

Whatever their guise, in small, almost traditional, styles used mainly for

lobster fishing or as deep, fat, almost ungainly fishing machines fitted as

seiners, scallop draggers, trawlers, longliners or swordfishermen, they can

be found all along Canada's east coast.

|

|

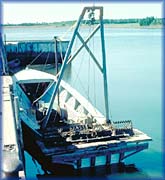

Northumberland Strait Boat

This open Northumberland Strait boat has been adapted to drag for scallops.

The steel mesh bags are dragged (towed) along the sandy bottom of the local

waters to scrape the shellfish from their beds. The winch is then used to

haul the scallops to the surface and onto the after shelf to be shucked.

(Courtesy: David Walker)

|

|